2014–15 Annual Report

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

This document is also available in PDF format.

ISSN 1925-7732

Letters

Excerpt from the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

Vision, Mission, Values

Commissioner's message

1 Operational Acheivements

2 Awareness and Engagement

3 Just the Facts

The Honourable Leo Housakos

Speaker of the Senate

The Senate

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour of presenting you with the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner’s eighth annual report for tabling in the Senate, pursuant to section 38 of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act.

The report covers the fiscal year ending March 31, 2015.

Yours sincerely,

Joe Friday

Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M. P.

Speaker of the House of Commons

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour of presenting you with the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner’s eighth annual report for tabling in the House of Commons, pursuant to section 38 of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act.

The report covers the fiscal year ending March 31, 2015.

Yours sincerely,

Joe Friday

Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

The federal public administration is an important national institution and is part of the essential framework of Canadian parliamentary democracy;

It is in the public interest to maintain and enhance public confidence in the integrity of public servants;

Confidence in public institutions can be enhanced by establishing effective procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoings and for protecting public servants who disclose wrongdoings, and by establishing a code of conduct for the public sector;

Public servants owe a duty of loyalty to their employer and enjoy the right to freedom of expression as guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and this Act strives to achieve an appropriate balance between those two important principles.

– Excerpt from the Preamble

Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

Our Vision

As a trusted organization where anyone can disclose wrongdoing in the federal public sector confidentially and safely, the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada enhances public confidence in the integrity of public servants and public institutions.

Our Mission

The Office provides a confidential and independent response to:

- disclosures of wrongdoing in the federal public sector from public servants or members of the public; and

- complaints of reprisal from public servants and former public servants.

Our Values

The Office operates under a set of values that defines who we are and how we interact with our clients and stakeholders:

Respect for Democracy

We recognize that elected officials are accountable to Parliament, and ultimately to the Canadian people, and that a non-partisan public sector is essential to our democratic system.

Respect for People

We treat all people with respect, dignity and fairness. This is fundamental to our relationship with the Canadian public and colleagues.

Integrity

We act in a manner that will bear the closest public scrutiny.

Stewardship

We use and care for public resources responsibly.

Excellence

We strive to bring rigour and timeliness as we produce high-quality work.

Impartiality

We arrive at impartial and objective conclusions and recommendations independently.

Confidentiality

We protect the confidentiality of any information that comes to our knowledge in the performance of our duties.

Commissioner’s Message

Commissioner

I am honoured to have been appointed Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada on March 27, 2015. This report will speak to our activities during the past fiscal year, most of which was under the direction of my predecessor, Mario Dion. We wish him well in his new endeavours and thank him for his four years of service to our organization.

As a matter of highest priority in my new position, I want to underscore my commitment to carrying out the important mandate given to our Office by Parliament to provide a safe, confidential and trustworthy means of disclosing wrongdoing in the public sector and to help protect public servants against reprisal.

We have solid experience to build upon, but we also have much work ahead of us. Under the guiding principles of clarity, consistency and accessibility, I want to provide to public servants and to all Canadians, the support they need to make confident and informed decisions about coming forward to our Office. Our goal is to strengthen the trust in our public institutions and in public servants, by building a robust, fair and independent whistleblowing regime. With a strong team of dedicated professionals working together to achieve this goal, I am confident of our ability to continue to effectively deliver our sensitive and important mandate.

Joe Friday

Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

Chapter 1 – Operational achievements

Our Office serves a key role in maintaining a high degree of public confidence in the federal public sector. This enhanced confidence is achieved by having a professional and independent institution capable of providing a safe and confidential space for federal public servants and Canadians to report wrongdoing without fear of reprisal. This year, we have continued to build on our past achievements and further strengthen our operational processes through our commitment to excellence.

Part of our Office’s core mandate is to receive, review and investigate disclosures of wrongdoing in a fair and timely manner. In cases of founded wrongdoing, a case report of findings with recommendations to the chief executive for corrective action is tabled in Parliament.

The Office is guided at all times by the public interest and the principles of natural justice and procedural fairness.

Founded cases of wrongdoing

In 2014-15 we tabled our ninth and tenth case reports in Parliament, as required under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act). These reports continue to demonstrate the extent of our mandate and our approach to implementing it as effectively as possible, as well as the breadth of the definition of wrongdoing.

Partisan Hirings

Our first case report this year found that the former Chief Executive Officer of the Enterprise Cape Breton Corporation (ECBC), which is a Crown Corporation, committed a serious breach of the organization’s code of conduct by appointing four individuals with publicly known ties to political parties into executive positions at ECBC. All were selected with little or no documented justification, without formal process and devoid of any demonstration that the appointments were merit-based. Federal organizations are required to be impartial and politically neutral. The former Chief Executive Officer did not act, in the words of the ECBC’s own code of conduct, in a manner so scrupulous that it bears the closest public scrutiny. The main shortcoming identified in this case was ECBC’s ambiguous recruitment and selection guidelines. ECBC’s Board of Directors has since approved a new Recruitment and Selection Process Policy.

Flying Overweight Aircraft

The second case report this year involved the Ottawa Air Section (OAS) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Air Services Branch (ASB). Our investigation found that the OAS contravened the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CAR) by making false entries in Aircraft Journey Log books and flying overweight. Due to the incorrect information in the log books, the RCMP could not ensure that its aircraft were being operated within the weight and balance limits.

Before our investigation began, the RCMP had already begun to address some of the allegations by way of Corrective Action Plans. Since this type of contravention of the CAR represents a serious matter of public interest, we continued the investigation and tabled the case report of founded wrongdoing in Parliament, despite the Corrective Action Plans.

The RCMP acted on the findings brought forward by our investigation and continues efforts to correct them through ongoing engagement with Transport Canada and with reminders to employees of their legal obligation under the CAR.

The full reports, as well as all other case reports we have tabled in Parliament, are available on our website.

Reprisals

The second part of our mandate gives us the exclusive jurisdiction to deal with reprisal complaints. Reprisals are defined as adverse actions taken against a public servant or former public servant for making a disclosure or for cooperating in an investigation into a disclosure. If, at the conclusion of an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe a reprisal has taken place, the Commissioner may apply to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal (the Tribunal) for a determination on whether a reprisal occurred. The Tribunal can order disciplinary sanctions against those who commit reprisal actions and comprehensive remedies for reprisal victims.

Applications to the Tribunal

In 2014-15 we referred three cases to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal.

In June 2013, we tabled a case report before Parliament with a finding of wrongdoing against the former President and Chief Executive of a small Crown corporation, Blue Water Bridge Canada (BWBC). The corporation operates and maintains an international bridge located between Canada and the United States.

Shortly after making the disclosure of wrongdoing to our Office and participating in our investigation, three senior employees of BWBC were unexpectedly dismissed from their employment.

The employees immediately filed reprisal complaints with our Office, and we launched an investigation. At the conclusion of our investigation, the Commissioner had grounds to believe that all three employees were victims of reprisal as a result of the disclosure and participation in our investigation, and he applied to the Tribunal for a hearing.

A hearing before the Tribunal is a public process that is similar to a trial, where the Commissioner, the complainant and the employer each present their evidence, testify and call their witnesses.

A few days after the start of the hearing, negotiation talks between the complainants and their former employer resulted in an “out-of-court” settlement, which resolved the issues in dispute and ended the hearing. The Commissioner supported the parties in their negotiation efforts and endorsed the settlement as a satisfactory conclusion to the complaints. The terms of the settlement are confidential.

Operational statistics

We continue to measure trends and movement within our caseload. This ongoing monitoring allows us to strategically plan our resources to effectively fulfill our mandate.

As mentioned in our previous annual report, the Office is better equipped to measure these trends and movements, now that we have been in operation for eight years. While these statistics are a snapshot of the Office’s annual workload, analyzing trends over time allows the Office to make informed decisions regarding its ongoing research, outreach and engagement strategies, and operational policies.

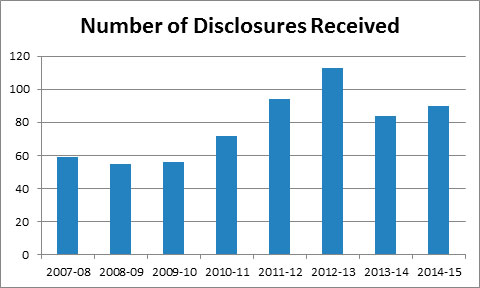

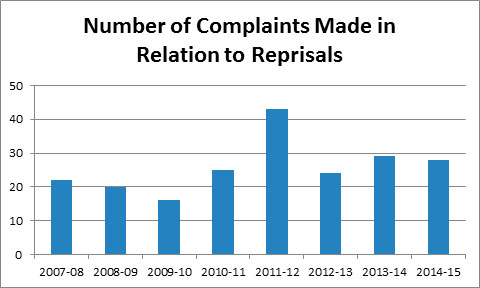

The number of disclosures made to our Office has increased to 90 from 84 the previous year; this is well above the annual average of 78 disclosures since 2007-08. The number of complaints of reprisals is 28, down from 29 the previous year; yet this is slightly above the annual average of 26 complaints, since 2007-08.

Text Version

This bar graph shows the number of disclosures received from fiscal years 2007–08 to 2014–15. 2007–08 to 2009–10 had between 40 and 60 disclosures. 2010–11 started to rise to between 60 and 80, 2011–12 rose to between 80 and 100. The peak is in 2012–13 with between 100 and 120 disclosures. 2013–14 and 2014–15 then dropped slightly to between 80 and 100.

Text Version

This bar graph shows the number of complaints made in relation to reprisals from 2007–08 to 2014–15. 2007–08 had between 20 and 30 complaints. 2008–09 and 2009–10 had between 10 and 20. 2010–11 increased to between 20 and 30 and 2011–12 peaked at between 40 and 50. Fiscal years 2012–13, 2013–14, 2014–15 all had between 20 and 30 complaints.

| Summary of new files received in 2014-15 | ||

|---|---|---|

| General Inquiries | Total number of general inquiries received | 194 |

| Disclosures | Total number of new disclosures of wrongdoing received | 90 |

| Reprisals | Total number of new reprisal complaints received | 28 |

Summary of activity 2014-15

| Disclosures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total number of disclosures of wrongdoing | 125 | |

| Number of disclosures of wrongdoing carried over from previous year | 33 | |

| Number of disclosures of wrongdoing received in 2014-15 | 90 | |

| Number of disclosures of wrongdoing (reconsideration) received in 2014-15 | 2 | |

| Completed disclosure files | 86 | |

| After admissibility review | 71 | |

| After investigation | 13 | |

| Number of files resulting in a founded case of wrongdoing | 2 | |

| Active disclosure files as of March 31, 2015 | 39 | |

| Currently under admissibility review | 33 | |

| Currently under investigation | 6 | |

| Reprisals | ||

| Total number of reprisal complaints | 43 | |

| Total number of reprisals carried over from previous year | 12 | |

| Number of reprisals received in 2014-15 | 28 | |

| Number of reprisals (reconsideration) received in 2014-15 | 3 | |

| Completed reprisal files | 27 | |

| After admissibility review | 18 | |

| After investigation | 5 | |

| After conciliation | 1 | |

| After being sent to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal | 3 | |

| Active reprisal files as of March 31, 2015 | 16 | |

| Currently under admissibility review | 4 | |

| Currently under investigation | 10 | |

| Currently under conciliation | 1 | |

| Currently before the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal | 1 | |

| Referrals to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal | ||

| Total number of cases referred to the Tribunal in 2014-15 | 3 | |

Note: Each disclosure and reprisal file may contain one or a number of allegations of wrongdoing

Service Standards

On April 1, 2013, we implemented service standards in order to provide greater transparency and certainty to our stakeholders, as well as to have an objective means of measuring our own performance. These service standards were introduced as part of a larger initiative to identify opportunities for efficiencies and to ensure that each file is treated in a timely fashion.

This is the second year that we have worked with the new service standards that were introduced in our 2012-13 annual report. The Act already provides a 15-day time limit for us to determine what action to take on a complaint of reprisal, but in addition to this, we applied the following standards to new files. Subject to exceptional circumstances:

- General Inquiries will be responded to within one working day;

- A decision whether to investigate a disclosure will be made, following full analysis and legal review, within 90 days of a file being opened;

- Investigations will be completed within one year of being launched.

For 2014-15, all targets established for service standards were met.

Summary of results 2014-15

| Service Standard | Target | Result |

|---|---|---|

| General Inquiries responded to within 1 working day | 80% | 99% |

| Decision whether to investigate a disclosure made within 90 days | 80% | 84% |

| Investigations completed within 1 year | 80% | 86% |

In addition to tracking compliance with our service standards, we have put in place internal mechanisms to monitor the performance of the Office’s handling of cases, including detailed quarterly reports on operational performance. These internal monitoring reports support the Office by providing a strategic overview of our operational performance; assessing and tracking operational results, organizational goals, and resource allocation using monthly and quarterly indicators; and identifying new policies, processes or procedures to assist in the fulfillment of our responsibilities under the Act.

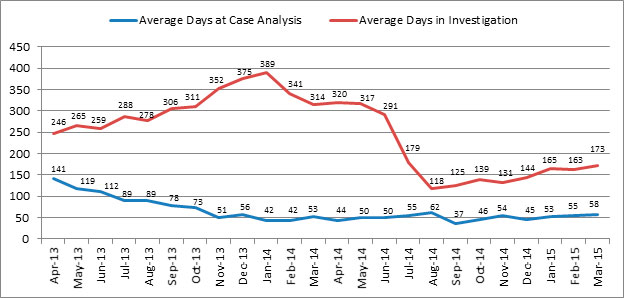

Average Number of Days Current Files Have Been Open at Each File Stage

April 2013 – March 2015

Text Version

This line graph shows the average number of days current files have been open at each file stage. The Y axis shows the average number of days from 0 to 450. The X axis shows the month and year from April 2013 to March 2015. On the first line, average days at case analysis starts at 141 in April 2013, 119 in May 2013, 112 in June 2013, 89 in July and August 2013, 78 in September 2013, 73 in October 2013, 51 in November 2013, 56 in December 2013, 42 in January and February 2014, 53 in March 2014, 44 in April 2014, 50 in May and June 2014, 55 in July 2014, 62 in August 2014, 37 in September 2014, 46 in October 2014, 54 in November 2014, 45 in December 2014, 53 in January 2015, 55 in February 2015 and 58 in March 2015.

On the second line, average days in investigation starts at 246 in April 2013, 265 in May 2013, 259 in June 2013, 288 in July 2013, 278 in August 2013, 306 in September 2013, 311 in October 2013, 352 in November 2013, 375 in December 2013, 389 in January 2014, 341 in February 2014, 314 in March 2014, 320 in April 2014, 317 in May 2014, 291 in June 2014, 179 in July 2014, 118 in August 2014, 125 in September 2014, 139 in October 2014, 131 in November 2014, 144 in December 2014, 165 in January 2015, 163 in February 2015 and 173 in March 2015.

Chapter 2 – Awareness and Engagement

This year, as in previous years, we proactively engaged with public servants. The Commissioner, and PSIC staff, gave many presentations at various events across the public service including conferences, staff meetings, executive committee meetings, working group learning days, the Interdepartmental Network on Values and Ethics and a webcast co-hosted by the Federal Youth Network and the Canada School of Public Service. We also hosted delegations from the Philippines, China, South Africa and Italy, all with the purpose of sharing information on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act and the role of our Office.

Face to face interactions are an excellent way to build awareness, but this year we also focused our efforts on leveraging Web 2.0 tools. We re-launched our corporate Twitter account and created a Youtube channel to showcase our new video, which will be the first in a suite of videos to help explain the intricacies of the Act. We also developed a GCpedia page (the internal government wiki) on the whistleblowing regime for public sector employees.

The video we launched in December gives a summary of what wrongdoing and reprisals are under the Act in a fresh, easy-to-understand and approachable format. The video was shared with the heads of all federal departments, agencies and crown corporations as well as the senior officers responsible for disclosures of wrongdoing within these organizations and the Canada School of Public Service. We hope it will be an engaging way to help increase understanding of the Act and the regime as a whole.

In addition to the video we created several other informational pieces that public sector organizations are welcome to use or borrow for special events. PSIC’s entire suite of communications materials can be found on our website at www.psic-ispc.gc.ca/en/psic-resources-download.

Union Collaboration

Public sector unions are a key stakeholder within the Canadian whistleblowing regime, as they provide specialized advice, counseling and support services to their members, and they serve as a trusted avenue for public servants to raise issues of concern within their workplace. While the Act does not include any express provisions related to unions, some unions have been involved in various capacities in a number of disclosures of wrongdoing. They have experience in assisting their members to consider and evaluate options for disclosing wrongdoing alleged to have occurred in the public sector and for submitting complaints of reprisal to our Office that resulted from a protected disclosure.

Our external Advisory Committee, which was created in 2011, includes union representatives who serve a key function of providing advice on initiatives and issues that relate to the Act and more specifically to our mandate. This year, the Association of Canadian Financial Officers joined our Advisory Committee, and spearheaded a joint project with us that aims to collaborate with the union’s labour relations advisors and its executives on matters relating to the role of our Office in the disclosure and reprisal regime, as well as to identify future information and awareness tools that could further assist the union and public servants. This project is continuing to be implemented into fiscal year 2015-16, and we look forward to the outcomes of our work together. ting complaints of reprisal to our Office that resulted from a protected disclosure.

Our external Advisory Committee, which was created in 2011, includes union representatives who serve a key function of providing advice on initiatives and issues that relate to the Act and more specifically to our mandate. This year, the Association of Canadian Financial Officers joined our Advisory Committee, and spearheaded a joint project with us that aims to collaborate with the union’s labour relations advisors and its executives on matters relating to the role of our Office in the disclosure and reprisal regime, as well as to identify future information and awareness tools that could further assist the union and public servants. This project is continuing to be implemented into fiscal year 2015-16, and we look forward to the outcomes of our work together.

Chapter 3 – Just the Facts

Ensuring that public servants have a clear understanding of the role of our Office and the complexities of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act remains a key challenge. This chapter addresses some recurring questions we receive and highlights some lesser known parts of the Act.

You Have a Choice

Did you know that the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner is just one of the options public servants have if they want to make a disclosure of wrongdoing in the federal public sector?

Public servants can disclose wrongdoing directly to our Office, to a supervisor, or to the designated senior officer for disclosures of wrongdoing within their organization. You do not have to exhaust internal mechanisms first before coming to our Office.

Neither supervisors nor senior officers are required to report disclosures to us. Only disclosures of wrongdoing made directly to our Office could potentially end up reported to Parliament in a case report.

Public servants who have made a disclosure of alleged wrongdoing to their supervisor or senior officer, and then subsequently make a complaint of reprisal to our Office are afforded protection from reprisal under the Act.

The Treasury Board Secretariat, in its own annual report, provides statistical information on disclosures made internally to organizations and provides information on its implementation of the Act. You can read the annual report and find other useful information by going to www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/ve/pda-eng.asp

What is “Gross” Mismanagement?

One of the elements of the definition of wrongdoing in the Act is gross mismanagement. This can mean different things to different people. Some of the factors that our Office considers when reviewing and investigating cases of gross mismanagement are:

- The deliberate nature and frequency of the wrongdoing;

- The impact on the wellness of employees;

- The impact on the ability of an organization, office or work unit to carry out its mandate; and

- The impact of the wrongdoing had on the public interest and trust in the organization.

Our published case reports can help provide examples of founded cases of gross mismanagement as well as other wrongdoings that fall under the Act. They are available on our website at: www.psic-ispc.gc.ca/eng/wrongdoing/casereports

Conciliation; A Viable Option

At any time, during the course of an investigation into a reprisal complaint, an investigator may recommend to the Commissioner that a conciliator be appointed to attempt to bring about a settlement between the parties. The decision to enter into conciliation remains with the parties and is entirely consensual. Parties to a conciliation process are eligible to receive funding for legal advice under the Act.

Conciliation unfolds very much like a mediation session. If the parties come to an agreement, the terms of the settlement must be referred to the Commissioner for final approval. If the Commissioner approves the settlement for a remedy to the complainant, the reprisal complaint is dismissed. Any information received by the conciliator remains confidential.

Conciliation, in appropriate cases, can be a fast and effective way to resolve reprisal complaints.

A Few Words in Closing

Certain aspects of the Act and the role of our Office can sometimes be misunderstood as evidenced in the media, in some of the alleged wrongdoings that come to our Office and in the conversations we have with federal public servants.

We continue to strive to clarify our role and the Act and welcome the opportunity to provide our suggestions to amend the legislation when it is reviewed. Our hope is that we can help change the culture that views whistleblowing in a negative way and reduce the fear of reprisal that goes along with it.